Lots of athletes suffer joint injuries and joint soreness, both human and animal. Because our joints are the mechanical links between two hard bones, they are exposed to considerable physical strain during exercise or activity. When joint overload, or excessive bending, or torque happens, joints get sore. Unless structural damage has occurred, the body’s homeostatic mechanisms are usually capable of restoring normalcy to a sore joint. However, if exercise is not discontinued for a sufficient length of time, flare-ups of joint inflammation can occur. Unfortunately, if this pattern of re-injury, recurrent soreness, and inflammation, with insufficient rest time is repeated frequently, the chances for more advanced arthritic change goes way up.

Lots of athletes suffer joint injuries and joint soreness, both human and animal. Because our joints are the mechanical links between two hard bones, they are exposed to considerable physical strain during exercise or activity. When joint overload, or excessive bending, or torque happens, joints get sore. Unless structural damage has occurred, the body’s homeostatic mechanisms are usually capable of restoring normalcy to a sore joint. However, if exercise is not discontinued for a sufficient length of time, flare-ups of joint inflammation can occur. Unfortunately, if this pattern of re-injury, recurrent soreness, and inflammation, with insufficient rest time is repeated frequently, the chances for more advanced arthritic change goes way up.

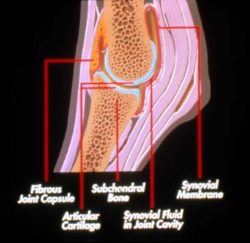

A way to help fight off the negative effects of athletic activity on our joints is to understand how joints work in the first place.

How Does a Joint Work?

A joint is made up of the “articular” cartilage that covers the end of two adjacent bones, as well as the surrounding soft tissues that help support the joint. These soft tissues include the strong fibrous joint capsule, with a soft inner layer of synovial lining tissue responsible for the manufacture of synovial, or “joint” fluid. Certain joints also contain ligaments that provide added support. The bone that underlies the articular cartilage also provides mechanical support to that cartilage.

The soft tissues of the joint have a blood supply and a nerve supply but the articular cartilage itself does not. Articular cartilage is therefore nourished by nutrients that diffuse into the cartilage from the joint fluid.

Because cartilage does not contain nerve endings it is never the source of pain in a sore joint. The pain or soreness of a joint comes from the soft tissues associated with the joint. In some very advanced cases of arthritis where the cartilage has been completely eroded down to bone, some pain derives from the bone itself.

Articular cartilage is a metabolically active tissue, and like other tissues in other organs, it continually undergoes some degree of tissue loss and tissue replacement.

The cartilage cells (chondrocytes) receive nutrition through the synovial fluid, and these cells make the different components of cartilage that provide it with its form, structure and strength.

Although there are several components, cartilage is mostly made up of considerable amounts of water, several different glycosaminoglycans (GAG’s), and a specialized collagen (type II) . Together all the ingredients make up what is called the “articular cartilage matrix.”

The GAG’s are sugar-like molecules that provide compressive stiffness to cartilage. This means that when you load a joint, the GAG’s are what provides the necessary strength to resist the compression. GAG’s structurally resemble glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, two components that are readily found in many joint health supplements.

The collagen provides tensile strength to articular cartilage. This is important when shearing forces are applied to a joint.

The different components of articular cartilage are continually being broken down due to wear & tear, as well as age. The cartilage cells continually make new components as replacements. Under normal conditions, homeostasis is maintained with the matrix component replacement being more than adequate to replace what’s lost. However, in athletes, and even in some daily activities for everyday humans, horses, and pets, our joints take a beating and get sore, and we need the best possible solution for joint health and support.

Understanding how a joint functions as a system helps us think about how to best treat them, both reactively and preventatively. Next, we’ll discuss the specific causes of soreness and gain a good understanding of how to fight it.

Comments are closed